The present downturn in the OSV market has cost the industry an astonishing € 41bln. Surprisingly little has been done to restore the imbalance in demand and supply of vessels. With assets build to last for 25 years the problem will be solved in a slow and natural order but obviously at great cost to all involved in the supply chain. Remko de Boer, the author of this article, believes that a solution is available that restores asset values and brings the industry back to sustainable levels. A solution which takes out 1100 vessels from the market at no cost to their owners. The solution being an industry fund setup to unite all stakeholders. The ultimate bill is covered by a small add-on tax on charter income to cover the quick restoration of the supply and demand in OSV vessels.

The solution to get out of the present downward pricing spiral is to restore the balance in supply and demand in the market. The warm /cold stacking efforts have not been sufficient, and more impactful methods are required. This means taking larger numbers of vessels off the market and controlling their re-entering of the market.

An appropriate question in this matter is: ‘Who will be picking up the bill?’

Charter behaviour

Assume a situation where any ship owner can sell any of their assets for an honest and realistic price. Honest when considering the old linear depreciation scheme over 25-year period and realistic when establishing deductions for rework to bring an asset to an acceptable working standard.

Having the free choice to hand over a vessel for an honest price will immediately change the book value of all vessels. With the improved book value, operator balance sheets and their solvability also changes very quickly. With the sole existence of the fund and determination of the OSV sector to solve the present situation, there is no reason why we wouldn’t see a different charter behaviour.

From ‘better take this low rate to

prevent further losses’ towards

‘I only want to engage for a fair price’.

Naturally, this is easier said than done, but an industry fund created for the purpose of actively buying vessels off the market will stabilise the market and smooth out the peaks and troughs of market day rates.

Collective approach

A collective approach in the OSV market has not yet been realised due to the fact that it is a global market with large regional differences and many local players. On a government level it is not uncommon to allocate multibillion-euro funding to, as an example, persuade farmers to stop their business or save merchant banks or airline companies as this makes economic sense. There is no such thing as an OSV government, but we do have global institutes who, long term, have been financing a sector which overnight lost a value of 41 billion euro.

Not only will this initiative restore the value of their shipping portfolios but the expenditures on reorganising the sector will bear interest and will be paid back in full.

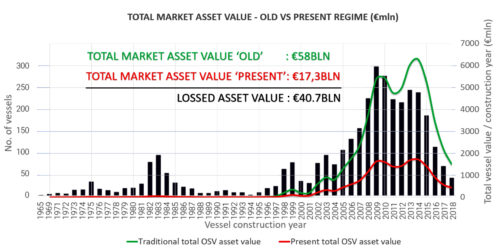

What about €41 bln? Let’s do the Arithmetic. According to Clarkson Offshore Intelligence Network by the analysis done by AlixPartners there are approximately 3500 vessels worldwide active in the OSV segment. According to Pareto Securities Equity Research the depreciation scheme of PSV’s show a remaining value of 16% in year 0 and 7,5% in year 4.

Guided by OSV newbuild values derived from Clarksons OIN database for PSV’s and AHTS type of vessels we can assume an average value of € 37mln for a newbuild OSV. Applying Pareto’s traditional and present vessel valuation scheme whilst considering an annual 1,5% inflation on newbuild prices, the following graph can be made:

Multiplying the vessel values times the numbers provides an approximate old and present valuation of the world wide OSV fleet. This shows an astonishing loss of € 41bln euro.

1100 Vessels

According to the analysis made by AlixPartners based on Clarksons Offshore Intelligence Network data, the market needs to take approximately 1100 vessels out of the market to match supply and demand. The question is which 1100 vessels? It is important that this selection is solely being made by the shipowner primarily based on his financial situation and targeted position in the market.

For vessels older than 25 years there is no incentive to trade in as there is hardly any difference between old and present depreciation schemes. Newer vessels will deliver more cash but takes away the earning power of operators in the new market with restored balance. It can be argued that the majority of the vessels traded in will be constructed somewhere between 1996 – 2008. Conveniently the market volume of OSV’s in that segment totals to 1100 vessels.

When assuming that these vessels are likely candidates to be traded in what kind of means are required to pay for this? Based on a linear depreciated scheme, the average value in that segment is €11,25 mln whilst the present vessel value is estimated around €3,75 mln.

When doing the mathematics, 1100 vessel can be taken out of the market at an average cost of €9 mln per vessel over a 7-year period. The total funds required to buy and process these vessels are covered by an add-on tax percentage on charter income of 10%.

The revenue stream coming from add-on taxation would stem from an industry wide agreement that OSV vessel charters will be imposed a revival fund add-on tax of 10%. This shifts the bill to the charters who over the last 5 years have been profiting from the extreme downward pricing spiral. Although not an attractive proposition for this group, they cannot deny that they also have an interest in a strong and resilient supply chain to support their businesses.

Of course, the above is a high-level analysis, but can it be considered a sufficiently accurate representation as the interests at stake ~€41bln exceeds by far the cost for recovery.

The largest stakeholder, the financial institutes, naturally would claim the improved revenue stream to cover outstanding debts. This would have to be monitored to ensure it does not turn out counterproductive to the objective of revival. To revive the industry the funds should also be directed to the shipowners in order to consolidate their businesses and set for future growth.

To make the above analysis viable, commitment would have to be sought from financers and operators to participate in this scheme so as to initiate solidarity. Only with the majority of operators agreeing on this way forward change can be expected. Fun or fairy tale?